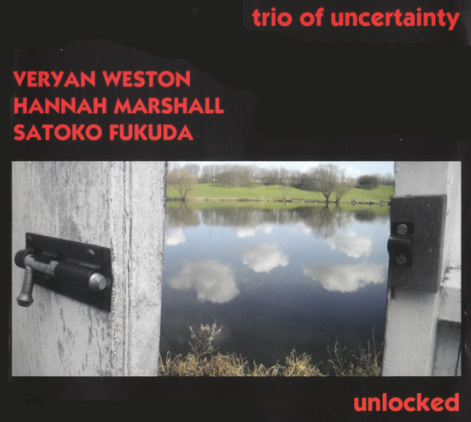

"Violinist Satoko Fukuda, cellist Hannah Marshall, and pianist Veryan Weston all have extensive classical training - no surprise, give the history of their instruments. As the Trio of Uncertainty, their like-minded backgrounds allow them a remarkable sense of ensemble, which in this case translates into an acute alertness to compositional parameters - that is, an intuitive reaction to what the others are doing at any given moment intended to provide a balance of parts, flexibility of foreground/accompaniment, a cohesive flow of details, and a sustained architecture" ART LANGE - POINT OF DEPARTURE 2007

"This disc is haunting and lyrical, with some exquisite counterpoint and dynamics. For a player with such a density of ideas, Weston has always struck me as particularly bouncy and effervescent, an apparent contrast marvelously built in to his approach. Such an amazing listener, too, giving tons of space to the young Fukuda. The group language is intense, with racing triple helixes here, limpid pools there, and occasional moments of somberness like those hear in a Bartok small group." JASON BIVINS - SIGNAL TO NOISE 2008

"Certainly it will be the unadorned sound of the trio plus their musical syntax that immediately strikes listeners, and which has the most effect on their reaction to the music. This sounds like a trio playing some mutant form of chamber music, which indeed it is. There are frequent passages on which the three could be playing a contemporary composition rather than improvising. Largely, this is due to Satoko Fukada's classically trained violin. ... The CD's front cover photo shows a peeling door that is unbolted and ajar, revealing a dreamlike pastoral landscape beyond, which features cotton wool clouds reflected in the tranquil surface of a river. Somehow, very fitting to the mood conjured up by the music." JOHN EYLES - ALL ABOUT JAZZ 2009

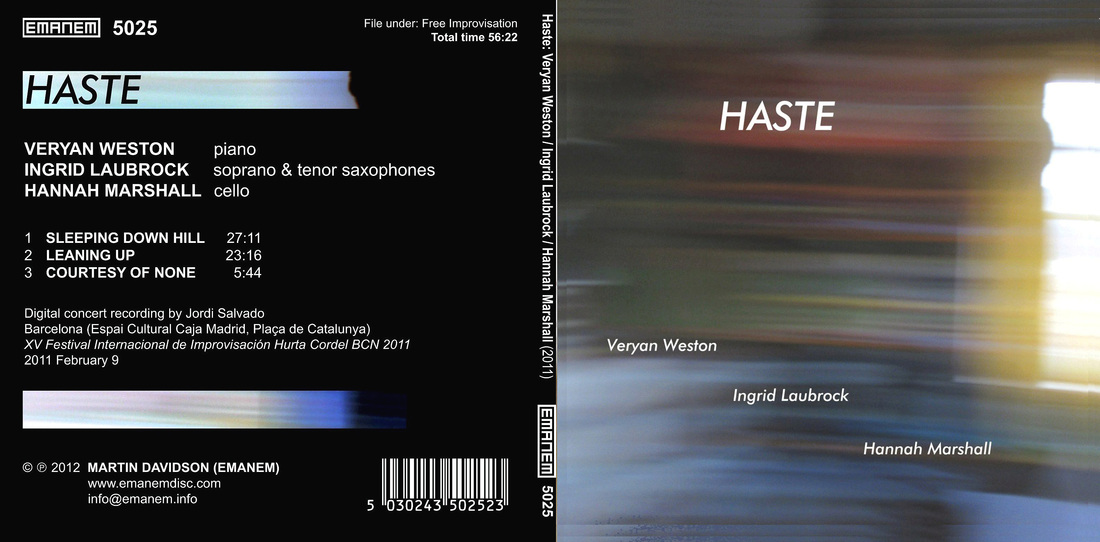

"....................That notion of speed is central here, a principle that asserts itself within a few minutes in the opening Sleeping Down Hill, the band assuming lift-off after a series of individual entries posed almost as questions, e.g., 'how much extraneous sound can be specifically heard through a bowed or blown harmonic?' Speed, as suggested, comes in two forms: one celebratory in which three very quick players throw off articulated runs that blur in the ear, clouds of sound playing at the edges of cognition. When it's a moment of actual haste, it's an up-rush of data in which the combined results of individuals' fingers and thoughts might deliberately confound one another, resulting in new fractures and new meanings. While Sleeping Down Hill assumes a volume that might be thought of as comfortable, Leaning Up and the brief Courtesy of None often work at very low levels in which the attention already demanded by speed is further attenuated. It's work (for musician and listener alike) that consistently surprises, whether it's Laubrock's articulation (like a gentle machine gun), Weston's at once billowing and blistering keyboard passes, or Marshall's eerily evasive knitwork that simultaneously links and dissolves the myriad connections in the music. It's free improvisation of rare consonance." STUART BROOMER - POINT OF DEPARTURE 2012

"It's an odd name, perhaps, for an album that starts out slowly and hesitantly, but it doesn't take long for things to get cooking. Soprano and tenor saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock first got together with pianist Veryan Weston a few years ago to work on Steve Lacy tunes before joining his existing duo with cellist Hannah Marshall and flying free. But there's still a Lacy-like rigour to their explorations of interval and line in this set recorded live in Barcelona last year. The ear for pitch is acute and the interactivity impressive throughout, with Marshall's impeccable timing and skill for finding strong yet subtle gestures a noticeable asset in navigating the complex, high-speed exchange of ideas between Laubrock and Weston, who proves once again that there's still plenty of mileage to be had from a piano without having to delve inside it and fiddle with the engine." DAN WARBURTON - THE WIRE 2012

"It's an odd name, perhaps, for an album that starts out slowly and hesitantly, but it doesn't take long for things to get cooking. Soprano and tenor saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock first got together with pianist Veryan Weston a few years ago to work on Steve Lacy tunes before joining his existing duo with cellist Hannah Marshall and flying free. But there's still a Lacy-like rigour to their explorations of interval and line in this set recorded live in Barcelona last year. The ear for pitch is acute and the interactivity impressive throughout, with Marshall's impeccable timing and skill for finding strong yet subtle gestures a noticeable asset in navigating the complex, high-speed exchange of ideas between Laubrock and Weston, who proves once again that there's still plenty of mileage to be had from a piano without having to delve inside it and fiddle with the engine." DAN WARBURTON - THE WIRE 2012

HASTE..........C a f e O t o s a m p l e

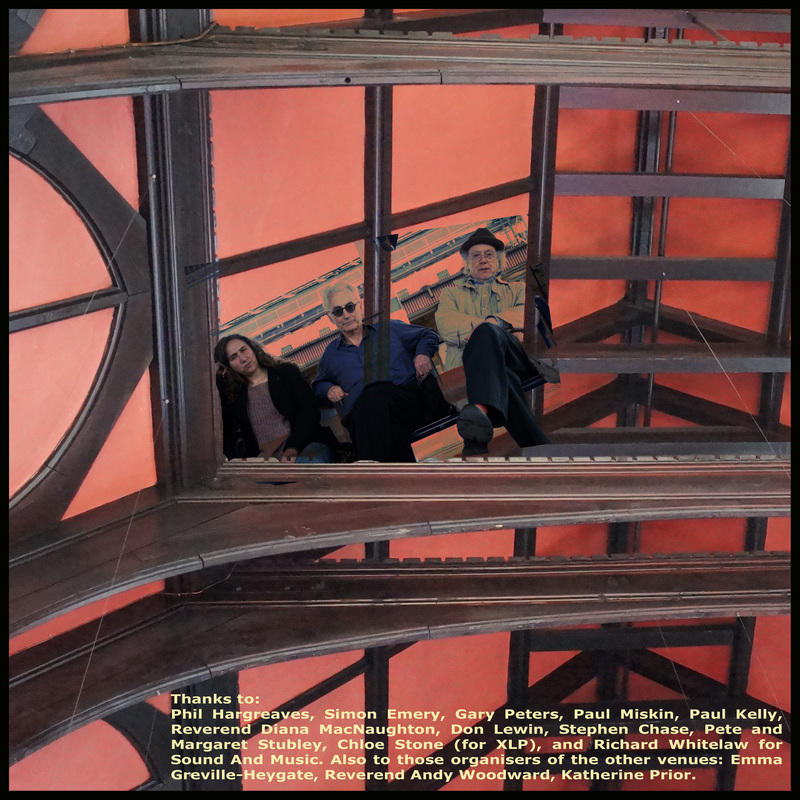

THE TUNING OUT TOUR

A UK wide tour of music that happened in 2014 which explored new territories in tuning using tracker action pipe organs and re-tuned string instruments. A released recording of selected performances will be released soon on EMANEM 5207.

Veryan Weston – Tracker action organs

Jon Rose - Violins

Hannah Marshall - Cello

‘Tuning Out’ is series of concerts taking place around the UK, which will invite a listening public to visit some wonderful instruments around the UK & re-imagine the nature of pitch relationships. The music will explore the lesser chartered areas of microtones, unequal temperaments and unusual instrumental tunings.

The project involves three musicians who question the rules of equal temperament in their own different ways.

They will be making use of some of the UK’s many underused tracker - action pipe organs, and using re-configured and re-tuned string Instruments.

Over several concerts in diverse areas of the country from Liverpool to London, Newcastle to Brighton, audiences can expect to be part of a rich sonic experiment, and have the chance to hear extraordinary instruments where new tunings open a world for new harmonies and colours that have, until now, remained locked away un-played.

Veryan Weston - long term explorer of underused and ancient instruments and Jon Rose – re-builder and re-thinker of the instrumental properties of the Violin, have been collaborating for the last 10+ years creating recordings and concerts that re-invent possibilities of how instruments can sound, and who use altered tunings as a primary avenue for improvisation.

They invited cellist Hannah Marshall - whose recent album Tulse Hill explores shifting de-tuned open string patterns, to join them in this collaboration.

Each Musician has written text giving some insight into the background of the tour and the music that will be made:

Veryan Weston

In many churches in England there are organs....they go with the Service and are a big part of the Christian ceremony and have been for hundreds of years. Many of the spaces are known to be great for singing in because of the hard stone reflective surfaces.....you get all that natural reverb which helps to imbue the atmosphere with a religious vibe.

Likewise the organ is an extra additive and enhancer, especially the big Baroque machine which can add a good squelch to any religious event.

But inside of all this more pious extreme are the smaller organs discreetly and modestly providing support to smaller and more intimate religious settings. As well as this there are the mechanics of an organ which affect the overall sound of an instrument and how that sound can be articulated. The earliest possible organs were completely mechanical and these are the ones I am interested in....these are called tracker action organs.

This system is entirely mechanical apart from having these days an electrical pump for blowing air in to the bellows in order to make each pipe speak. Many of these are now considered too costly to maintain and so get replaced either completely by digital keyboards or refurbished and modified with a newer pneumatic action.

However, the tracker action is the organ where there is a more direct physical relationship between the instrument and the player. With the bigger instruments it becomes increasingly a physical struggle to have a lot of stops pulled out.

With the smaller chamber-sized organs this is not really too much of a problem. When each stop is very carefully and slowly pulled while a key is pressed, a myriad of uncertain transitional stages of sound is produced....at first you get just the breath, then a glimmer of sound, often in a different pitch to the final key pitch...this different pitch can be a microtone away from the final pitch or can be some kind of harmonically related partial to the final pitch....and if the stop is further pulled, the volume increases before getting to its final full 'stop-out' destination.

So with different manuals (more than one keyboard) you can start to relate chords like this on one manual to chords like that on another, with stops that relate to only one of the keyboards....the resulting chords are sonically rich and uncertain and changeable depending on the minutest push or pull of a stop in transition.

So now with this project I have to find where these treasures are, and this can be difficult. I usually leave two questions on a church office answerhone: 'Does the church ever host music concerts that are open to the general public?'....the answer to this has been usually 'yes'. Second question: 'Does the church have a tracker action organ?' This usually prompts a reply in which I am referred to either the church organist - who still might not know the answer - or to the person who comes in occasionally to clean, maintain and tune the organ, who sometimes in fact does not exist.

Fortunately there is the National Pipe Organ Register which is reasonably up to date and is a remarkable feat of commitment considering the number of churches and churches with organs in the country. This register also explains what the mechanics of the organ are in each church.

So the first phase was to find numbers and ring round asking these two previously mentioned questions. The second phase, which is where I am at the moment, is to visit all the locations, meet the priest, caretaker, curate, reverend, father or warden and check the space to see if the organ is situated on ground level and at the front of the church, so it can accommodate Jon Rose and his acoustic violins and Hannah Marshall and her acoustic cello.

So far it has been much easier to get an open and positive response for putting on an event than ringing around venues that occasionally program contemporary music.

The church venue is very remote from most people's lifestyles now – I'm sometimes told that as few as 4 or 5 people come to the regular Sunday morning service. I could immediately see parallels with the sparsely attended new music gigs I have been involved in on occasion over the years. But the churches are still maintained and supported by the community who seem to like the idea that they are there as part of their history and culture....it's almost like some kind of reassurance that their own culture and heritage is being preserved.

So now churches are diversifying as much as they can to attract youth groups, creches, societies, activity groups and music concerts that are not necessarily 'sacred', and this way are trying to make links with a larger community outside their own often dwindling parish community.

I spoke with one person in Northampton who was helping host a feast which was completely open to all. I asked her if hungry (i.e. poor) people came to eat and she said 'no' but added they encouraged all kinds of people to attend, including those of other faiths and she proudly said there were even atheists who came. So the people at this church believed it was more important to be active socially and this also meant that they put on live music events....even like the one I was suggesting.

Upstairs in this same space on a mezzanine was a cute little Ken Tickell and Son tracker action chamber organ. It was modern - these organs are recognised for their attributes and merits over other systems and so are still being built - but nevertheless they always seem completely different from each other in shape, sound and dimension.

The project with Jon and myself has been in existence for several years now and we have made recordings which have explored tunings and differently built acoustic historical keyboards. This provides Jon with a more balanced foil both volume-wise and by giving a more loose and slippery approach to pitching. Getting in the cracks has always been something that cannot be possible with a finely tuned modern pianoforte in fixed equal temperament.

With this combination of instruments on this project there is the inclusion of not only the cello but more importantly, the cellist, Hannah Marshall who like ourselves is exploring the possibilities of retuning her instrument to give it a new sound. As so often with string instruments, those open strings give a quite clearly defined prescriptive character as to what is being played at many given times, so by changing the tuning of each string, the player is given a different set of playing options.

There it is....Thursday 6th March 2014....making my way back from Norwich, tired and worn out, where I had seen two organs and spaces; one in the centre of town in a converted 13th century hospital where the reverend did not seem so keen on the idea of having a concert. Her work had mostly been in prisons and she wanted to keep her over-stretched activities to a minimum, plus she expressed a dislike for contemporary music. What's more, she only gave me 15 minutes to get to know the organ and try out a few basic possibilities. When the 15 minutes was up, an excruciating fire alarm sounded in the church - which was the signal for me to finish from the Reverend Ratchet, I suspect.

Churches and tracker action organs have now been superseded -

Hannah Marshall

Within a few notes of any instrument being played, an amount of information is transmitted to the listener about the nature of the proceeding music. This is transmitted through the many different properties of a note, one of the most powerful being tuning.

Tuning is conveyed not just through one note’s relationships with another note, but also through the tuning of the note to itself, by the sounding of sympathetic strings, parts of a resonating chamber or the internal workings of the instrument. This provides vital timbral information about the pitch and tuning tradition that the musician and instrument is employing.

As a result of this information being received, often unconsciously by the listener, our ears approach the music/sound from a position about and what we think the music is; whether it’s ‘well’ played, historical, folk, modern or traditional, what era it might be representing & who the player is.

However, when the tonal relationships between pitches cover a range of unusual micro-tonal intervals, for the prevailing culture, the listener may find themselves spending more time than they thought working out what the music is, where it is going and what their feelings about it are, and so, a journey of discovery can begin.

I would like to suggest that when music can by-pass the assumptions and judgments of the listener there is a greater possibility for an ‘experience’ to occur. Of revulsion perhaps, or beauty, even revelation. This is surely a good reason to shake up and take apart those fundamental bricks of western music: tones and semi-tones, devoting some time playing in the depths of the spaces between.

By opening up the possibilities of quarter and eighth tones in pitch we are delving deeper into the inherent sonic properties of both string instruments and pipe organs. We will be opening a box of delights, and finding ways of carefully translating the sounds we find into a space with people listening and experiencing sound within it. A lot of tuning will be taking place on our tour, with some complex preparation and re-configuring of our own and borrowed instruments along the way. We will be venturing into un-chartered territory, letting pitches rub up against each other that normally stay firmly continents apart, playing in scattered regions of the UK from Newcastle to Norwich where the rich pickings of ancient places offer us a wealth of treasures to play with.

Jon Rose

Tchaikovsky is mainly remembered these days as an arch romantic who gave us such rollercoaster numbers as his violin concerto (which I took on as an improvisational challenge proposed by John Oswald and conducted by Ilan Volkov in 2006). But Pyotr's great moment of insight in my book is his observation - that the violin and the modern grand piano have nothing to do with each other.

To any string player who has tried to make the combination of grand piano and violin or cello work, the problem is daunting yet remains an unspoken conundrum in classical music circles.

Firstly, there is the problem of volume imbalance. The piano must be played Mezzo Piano (or quieter) and the string instrument must be blasting away at Double Forte like there is no tomorrow - if these two bastions of western classical music are to remain in the same ballpark. The usual solution is to mute the piano by closing the piano lid (almost) horizontal leaving a small gap by which the sound can escape – thus rendering the tone of the piano even more bland than usual.

Which leads to the issue of timbral ships passing in the night. If you line up a violin with an early Forte Piano (such as a Graf or Stein) as opposed to a modern Steinway, the problem disappears. The instruments start chatting away in both tone and timbre. The early pianos, like the harpsichord, have a plethora of buzz, grain, noise, rattle, and attack transient – a great combination for the basic saw tooth waveform of the bowed string. With the modern piano, all that good action movie stuff has been removed. While I was struggling as a kid through all THE repertoire by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and the rest, I knew there was something not quite right, I just didn't know back then what the problem was, because there were no other models available by which I could learn. Solution? If you want a good relationship between a violin and a modern piano – then stick a whole bunch of stuff in between the strings – prepare it – that's a guaranteed fix!

Now it's not every day you can get your hands on an historic Forte Piano (especially if you play improvised music), so over the years Veryan Weston and I have musically engaged with the alternative combination of small pipe organs and strings. Although tonally worlds apart, the two instrumental types talk to each other – they just do. It's the historical digestive system at work – guts, wind, pipes. Back to animal first principles.

Which brings me on to the big banana – tuning. Left to our own devices, most string players will try and play pure intervals – well at least we will tune the 5ths pure no matter what kind interval errors or horrors happen further along the way. As a music student, the given was that the piano was in tune and please will you try your best to get with the program. Then you discover later that you have been had. The bloody piano is always purposely out of tune, there's not a pure interval in the damn thing! The 5ths are all flat, the 3rds are all sharp. Further more, you can play in any key on the Joanna and all the intervals sound the same in all keys. What is the point of modulating from one key to another if it sounds exactly as out of tune as the key you just came from? No wonder I gave up playing classical music when I was 15.

Wand thus we turn to the cello. This is simply a superior instrument to the violin as pain, suffering, contortionism, deafness, arthritis, are not considered fundamental to either learning the thing or being able to play it when you have gone past… shall we say… a certain age. I am delighted and looking forward to crossing bows with the most excellent Hannah Marshall on this tour – a pleasure not previously experienced.

What about Scordatura I hear you say? Actually my hearing is not what it was, so maybe you didn't say that at all. I notice that Google has 227,000 results for scordatura, so I'll leave it there.

Jon Rose - Violins

Hannah Marshall - Cello

‘Tuning Out’ is series of concerts taking place around the UK, which will invite a listening public to visit some wonderful instruments around the UK & re-imagine the nature of pitch relationships. The music will explore the lesser chartered areas of microtones, unequal temperaments and unusual instrumental tunings.

The project involves three musicians who question the rules of equal temperament in their own different ways.

They will be making use of some of the UK’s many underused tracker - action pipe organs, and using re-configured and re-tuned string Instruments.

Over several concerts in diverse areas of the country from Liverpool to London, Newcastle to Brighton, audiences can expect to be part of a rich sonic experiment, and have the chance to hear extraordinary instruments where new tunings open a world for new harmonies and colours that have, until now, remained locked away un-played.

Veryan Weston - long term explorer of underused and ancient instruments and Jon Rose – re-builder and re-thinker of the instrumental properties of the Violin, have been collaborating for the last 10+ years creating recordings and concerts that re-invent possibilities of how instruments can sound, and who use altered tunings as a primary avenue for improvisation.

They invited cellist Hannah Marshall - whose recent album Tulse Hill explores shifting de-tuned open string patterns, to join them in this collaboration.

Each Musician has written text giving some insight into the background of the tour and the music that will be made:

Veryan Weston

In many churches in England there are organs....they go with the Service and are a big part of the Christian ceremony and have been for hundreds of years. Many of the spaces are known to be great for singing in because of the hard stone reflective surfaces.....you get all that natural reverb which helps to imbue the atmosphere with a religious vibe.

Likewise the organ is an extra additive and enhancer, especially the big Baroque machine which can add a good squelch to any religious event.

But inside of all this more pious extreme are the smaller organs discreetly and modestly providing support to smaller and more intimate religious settings. As well as this there are the mechanics of an organ which affect the overall sound of an instrument and how that sound can be articulated. The earliest possible organs were completely mechanical and these are the ones I am interested in....these are called tracker action organs.

This system is entirely mechanical apart from having these days an electrical pump for blowing air in to the bellows in order to make each pipe speak. Many of these are now considered too costly to maintain and so get replaced either completely by digital keyboards or refurbished and modified with a newer pneumatic action.

However, the tracker action is the organ where there is a more direct physical relationship between the instrument and the player. With the bigger instruments it becomes increasingly a physical struggle to have a lot of stops pulled out.

With the smaller chamber-sized organs this is not really too much of a problem. When each stop is very carefully and slowly pulled while a key is pressed, a myriad of uncertain transitional stages of sound is produced....at first you get just the breath, then a glimmer of sound, often in a different pitch to the final key pitch...this different pitch can be a microtone away from the final pitch or can be some kind of harmonically related partial to the final pitch....and if the stop is further pulled, the volume increases before getting to its final full 'stop-out' destination.

So with different manuals (more than one keyboard) you can start to relate chords like this on one manual to chords like that on another, with stops that relate to only one of the keyboards....the resulting chords are sonically rich and uncertain and changeable depending on the minutest push or pull of a stop in transition.

So now with this project I have to find where these treasures are, and this can be difficult. I usually leave two questions on a church office answerhone: 'Does the church ever host music concerts that are open to the general public?'....the answer to this has been usually 'yes'. Second question: 'Does the church have a tracker action organ?' This usually prompts a reply in which I am referred to either the church organist - who still might not know the answer - or to the person who comes in occasionally to clean, maintain and tune the organ, who sometimes in fact does not exist.

Fortunately there is the National Pipe Organ Register which is reasonably up to date and is a remarkable feat of commitment considering the number of churches and churches with organs in the country. This register also explains what the mechanics of the organ are in each church.

So the first phase was to find numbers and ring round asking these two previously mentioned questions. The second phase, which is where I am at the moment, is to visit all the locations, meet the priest, caretaker, curate, reverend, father or warden and check the space to see if the organ is situated on ground level and at the front of the church, so it can accommodate Jon Rose and his acoustic violins and Hannah Marshall and her acoustic cello.

So far it has been much easier to get an open and positive response for putting on an event than ringing around venues that occasionally program contemporary music.

The church venue is very remote from most people's lifestyles now – I'm sometimes told that as few as 4 or 5 people come to the regular Sunday morning service. I could immediately see parallels with the sparsely attended new music gigs I have been involved in on occasion over the years. But the churches are still maintained and supported by the community who seem to like the idea that they are there as part of their history and culture....it's almost like some kind of reassurance that their own culture and heritage is being preserved.

So now churches are diversifying as much as they can to attract youth groups, creches, societies, activity groups and music concerts that are not necessarily 'sacred', and this way are trying to make links with a larger community outside their own often dwindling parish community.

I spoke with one person in Northampton who was helping host a feast which was completely open to all. I asked her if hungry (i.e. poor) people came to eat and she said 'no' but added they encouraged all kinds of people to attend, including those of other faiths and she proudly said there were even atheists who came. So the people at this church believed it was more important to be active socially and this also meant that they put on live music events....even like the one I was suggesting.

Upstairs in this same space on a mezzanine was a cute little Ken Tickell and Son tracker action chamber organ. It was modern - these organs are recognised for their attributes and merits over other systems and so are still being built - but nevertheless they always seem completely different from each other in shape, sound and dimension.

The project with Jon and myself has been in existence for several years now and we have made recordings which have explored tunings and differently built acoustic historical keyboards. This provides Jon with a more balanced foil both volume-wise and by giving a more loose and slippery approach to pitching. Getting in the cracks has always been something that cannot be possible with a finely tuned modern pianoforte in fixed equal temperament.

With this combination of instruments on this project there is the inclusion of not only the cello but more importantly, the cellist, Hannah Marshall who like ourselves is exploring the possibilities of retuning her instrument to give it a new sound. As so often with string instruments, those open strings give a quite clearly defined prescriptive character as to what is being played at many given times, so by changing the tuning of each string, the player is given a different set of playing options.

There it is....Thursday 6th March 2014....making my way back from Norwich, tired and worn out, where I had seen two organs and spaces; one in the centre of town in a converted 13th century hospital where the reverend did not seem so keen on the idea of having a concert. Her work had mostly been in prisons and she wanted to keep her over-stretched activities to a minimum, plus she expressed a dislike for contemporary music. What's more, she only gave me 15 minutes to get to know the organ and try out a few basic possibilities. When the 15 minutes was up, an excruciating fire alarm sounded in the church - which was the signal for me to finish from the Reverend Ratchet, I suspect.

Churches and tracker action organs have now been superseded -

Hannah Marshall

Within a few notes of any instrument being played, an amount of information is transmitted to the listener about the nature of the proceeding music. This is transmitted through the many different properties of a note, one of the most powerful being tuning.

Tuning is conveyed not just through one note’s relationships with another note, but also through the tuning of the note to itself, by the sounding of sympathetic strings, parts of a resonating chamber or the internal workings of the instrument. This provides vital timbral information about the pitch and tuning tradition that the musician and instrument is employing.

As a result of this information being received, often unconsciously by the listener, our ears approach the music/sound from a position about and what we think the music is; whether it’s ‘well’ played, historical, folk, modern or traditional, what era it might be representing & who the player is.

However, when the tonal relationships between pitches cover a range of unusual micro-tonal intervals, for the prevailing culture, the listener may find themselves spending more time than they thought working out what the music is, where it is going and what their feelings about it are, and so, a journey of discovery can begin.

I would like to suggest that when music can by-pass the assumptions and judgments of the listener there is a greater possibility for an ‘experience’ to occur. Of revulsion perhaps, or beauty, even revelation. This is surely a good reason to shake up and take apart those fundamental bricks of western music: tones and semi-tones, devoting some time playing in the depths of the spaces between.

By opening up the possibilities of quarter and eighth tones in pitch we are delving deeper into the inherent sonic properties of both string instruments and pipe organs. We will be opening a box of delights, and finding ways of carefully translating the sounds we find into a space with people listening and experiencing sound within it. A lot of tuning will be taking place on our tour, with some complex preparation and re-configuring of our own and borrowed instruments along the way. We will be venturing into un-chartered territory, letting pitches rub up against each other that normally stay firmly continents apart, playing in scattered regions of the UK from Newcastle to Norwich where the rich pickings of ancient places offer us a wealth of treasures to play with.

Jon Rose

Tchaikovsky is mainly remembered these days as an arch romantic who gave us such rollercoaster numbers as his violin concerto (which I took on as an improvisational challenge proposed by John Oswald and conducted by Ilan Volkov in 2006). But Pyotr's great moment of insight in my book is his observation - that the violin and the modern grand piano have nothing to do with each other.

To any string player who has tried to make the combination of grand piano and violin or cello work, the problem is daunting yet remains an unspoken conundrum in classical music circles.

Firstly, there is the problem of volume imbalance. The piano must be played Mezzo Piano (or quieter) and the string instrument must be blasting away at Double Forte like there is no tomorrow - if these two bastions of western classical music are to remain in the same ballpark. The usual solution is to mute the piano by closing the piano lid (almost) horizontal leaving a small gap by which the sound can escape – thus rendering the tone of the piano even more bland than usual.

Which leads to the issue of timbral ships passing in the night. If you line up a violin with an early Forte Piano (such as a Graf or Stein) as opposed to a modern Steinway, the problem disappears. The instruments start chatting away in both tone and timbre. The early pianos, like the harpsichord, have a plethora of buzz, grain, noise, rattle, and attack transient – a great combination for the basic saw tooth waveform of the bowed string. With the modern piano, all that good action movie stuff has been removed. While I was struggling as a kid through all THE repertoire by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and the rest, I knew there was something not quite right, I just didn't know back then what the problem was, because there were no other models available by which I could learn. Solution? If you want a good relationship between a violin and a modern piano – then stick a whole bunch of stuff in between the strings – prepare it – that's a guaranteed fix!

Now it's not every day you can get your hands on an historic Forte Piano (especially if you play improvised music), so over the years Veryan Weston and I have musically engaged with the alternative combination of small pipe organs and strings. Although tonally worlds apart, the two instrumental types talk to each other – they just do. It's the historical digestive system at work – guts, wind, pipes. Back to animal first principles.

Which brings me on to the big banana – tuning. Left to our own devices, most string players will try and play pure intervals – well at least we will tune the 5ths pure no matter what kind interval errors or horrors happen further along the way. As a music student, the given was that the piano was in tune and please will you try your best to get with the program. Then you discover later that you have been had. The bloody piano is always purposely out of tune, there's not a pure interval in the damn thing! The 5ths are all flat, the 3rds are all sharp. Further more, you can play in any key on the Joanna and all the intervals sound the same in all keys. What is the point of modulating from one key to another if it sounds exactly as out of tune as the key you just came from? No wonder I gave up playing classical music when I was 15.

Wand thus we turn to the cello. This is simply a superior instrument to the violin as pain, suffering, contortionism, deafness, arthritis, are not considered fundamental to either learning the thing or being able to play it when you have gone past… shall we say… a certain age. I am delighted and looking forward to crossing bows with the most excellent Hannah Marshall on this tour – a pleasure not previously experienced.

What about Scordatura I hear you say? Actually my hearing is not what it was, so maybe you didn't say that at all. I notice that Google has 227,000 results for scordatura, so I'll leave it there.